I’m a holocaust survivor, and I’m extremely lucky to be alive.

In 1942, out of a population of 90,000 Jewish people in Slovakia, 60,000 were sent to death camps, over a 6 month period. However, because my father was an advisor on crop improvement, he was provided with an exemption. Had he not been, I would have been on one of those transports and I would have been murdered.

But in 1944, even though they were losing the war, Germany began making its final roundup of Jews in Slovakia. Hoping to buy us some time, my father paid a farmer to hide us in his attic, where we lived for 4 months. We had to be very quiet at all times, but I remember it was very hard to keep still, as I was only 7.

Unfortunately, they started broadcasting our names on the local radio, saying the penalty for whoever was hiding us was death, so the farmer had to ask us to leave, to protect his own family. And only 24 hours after we returned to our house, there was a knock on the door – it was 2 Gestapo officers and two young policemen, saying we were under arrest. Luckily, my parents were able to take a small suitcase with us, and my mother quickly took two child blankets from my bed and tied them to the suitcase, which later saved my life.

Then, we were taken to a local jail, where I lost my childhood, because I witnessed my parents being tortured. The police wanted to find out where all the valuables were, even though they had already been confiscated by the government years earlier. It was a horrific scene – I saw my parents’ backs black and blue and bloody. But my mother was extremely calm afterwards. Even though I was an absolute mess, she was able to comfort me.

We stayed overnight in a cell, and the next morning, we were taken to a transit camp, where we were separated from my father, and put in a dormitory of women and children. One morning, we all had to go down near the train platforms, where there were guards everywhere, pushing us forward. My mother said, ‘Don’t let my hand go, whatever you do,’, and I said to her, ‘We can’t go. We can’t go without Daddy!’ You see, my father was everything to me. He was just a tremendous person. We always played together, and he would take me on his bicycle in the fields. But my mother said, ‘Look, don’t worry, the men will be coming in the next transport.’

Then, we were pushed onto a cattle train, 100 to a carriage, with no windows and no electricity, and nothing inside except an empty bucket to be used as a toilet. And they bolted the doors. My mother put one blanket on the wooden floor and the other one around me, and it was very lucky we had those blankets because it was extremely cold. We were 5 days on that train, and of course, we were never told our destination, which was very frightening. Some of the women grew hysterical. We were also very hungry and thirsty, although twice we stopped at a station where they handed us in some bread, and replaced the bucket. But there was a third time when we stopped for about a day and the doors didn’t open and they didn’t give us anything.

50 years later, I found out our train went to Auschwitz on that day. But they didn’t want us because they had received orders to destroy the gas chambers and the crematoria, to hide the evidence, as the Soviet Army was approaching. So we were redirected to a labour camp back in Czechoslovakia, called Terezin, which was in a walled fortress.

At first, I was separated from my mother and put into the boys home, but I didn’t do well there because I couldn’t eat the food. It was such slop, made of an artificial material, and every time I felt it going down my throat, I threw up. As a result, I became very sick, and my mother was out of her mind because I was losing so much weight. But she’s a very strong person, and she approached the authorities to demand that I be able to live with her in the barrack, and eventually, they allowed me to. The food was still much the same, but my mother would sometimes risk taking an egg or a piece of meat from the farm where all the women had to work, even though they beat you badly if you were caught doing that. And in that way, she saved my life again.

My life kept on day by day. I never knew what was going on there, but it felt like living in a nightmare. We children couldn’t go outside because it was freezing, so I remember I spent a lot of time looking at one of the blankets, which had a repeating frieze of a desert scene on it, with a man leading a camel, and pyramids and palm trees. To me, it was a great novelty, and I used to make up games in my mind about the characters when I was missing my father, which I think was psychologically very good for me.

Very close to the end of the war, we had about 4000 evacuees arrive from other camps that were about to be liberated by the Allies and, incredibly, instead of letting these prisoners go, the German leaders had still made sure to move them to another camp. I witnessed absolutely horrifying scenes, of men getting off cattle trains who were like skeletons, but worse was when we looked inside and there were more men who had died because they hadn’t had any water or food. It was a maddening scene. Also, these men were infected with typhus and as a result, we had a typhoid epidemic just before the end of the war, and many more people died.

Finally, one morning my mother woke me up and said, ‘Come on, get dressed!’ And when I went out, there a was a commotion going on. People were running and running, and I saw the gate of the wall was open for the first time and people were calling out, ‘They’re gone, they’re gone. All the guards have gone.’ And so, we were liberated, by the Soviet Army.

For me, it was just joy, joy, joy, because I was going to see my father again. But when we got back home, he wasn’t there and I grew very upset. My mother said, ‘Don’t worry, Daddy will be on the next transport’, and every time there was a transport of survivors coming, she would take a small bus from our village to the capital of Slovakia, and hold up a piece of paper with my father’s name on it, hoping for news of him.

Finally, one day she came home very upset, and said that a man had approached her and said he had seen my father shot by a Nazi guard.

We had nobody left in our country, but my mother had a sister and brother-in-law in Australia and they wrote to her saying that I would have a better future if we migrated here. It was an exciting trip for a 9 year old boy, coming by boat, but all the time I was thinking about what it would be like if my father was with us. Then we came into Sydney Harbour, and the Harbour Bridge was there, which was a beautiful sight.

My mother owed £150 to her sister for the cost of the sponsoring us to migrate here. They were not pressing her for payment, but at the same time, they were fairly poor people and getting on in age, and this money was probably all their savings, so she felt very obliged to repay it. But she was only earning £4 a week, so she needed to work 3 jobs in order to be able to give them anything. So that she could be free to do that much work, I lived in a half orphans home. At first, I saw her once a week but she was so tired, I said to her, ‘I’ll ask the matron if I can ring you instead’, because it was a long way for her to travel to come and see me. So that was the arrangement for 4 years. Later, I left school so I could get a job to help her repay the debt. We were so poor, it was incredible. I used to wear hand me down clothes that people gave my mother, and even when I started work in an insurance company, I had to wear my school uniform pants at first.

But Australia was a great place, and it still is. Here, you can succeed, and my mother’s motto was, ‘Nothing is impossible. If you don’t get it the first time, do it again.’ And I adopted that same motto. First, I went to night school to study Accounting. Then, I went to work in an accountancy firm, and I progressed from there, working for Price Waterhouse, and finally starting my own practice.

You need to put in some hard work to succeed. My mother was traumatised, and so was I, and it takes a long time to get over these things, but there was no stopping us, and we finally became comfortable. Now, I’m married to a lovely lady and we’ve got 2 beautiful daughters and 3 grandchildren. I also work as a volunteer at the Sydney Jewish museum, where you can find the blanket that became so important to me.

I’ve also written a book about my life called ‘In Search of My Father’. I tell my story because I believe that it needs to be told.

If we don’t heed the stories of the past, these things can happen again and again.

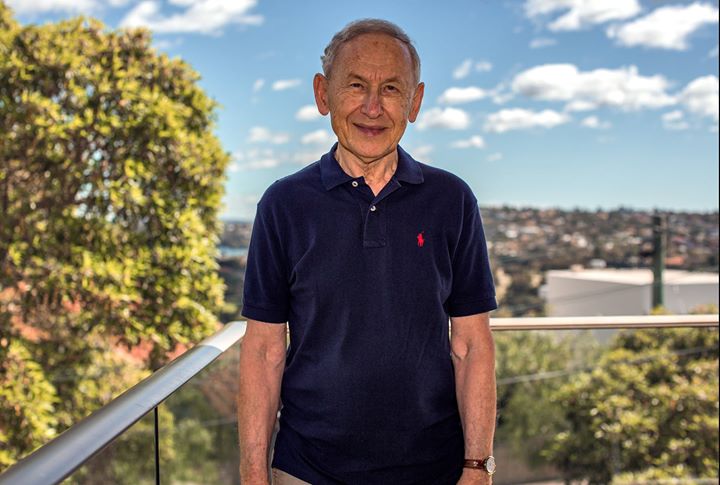

Paul

Arrived 1948

Czechoslovakia

Photographer: Mike Vlack www.instagram.com/mikevlack

……………

LIMITED STOCK. If you are thinking about getting copies of the New Humans of Australia book as Christmas presents, please order now. We only have approximately 200 books left.

Special price for pack of 3 – the perfect xmas gift ????????????

www.newhumansofaustralia.org/store